Is peace, for example, simply the absence of war? How is it linked to conflict? Furthermore, how are the two such an integral part of discourse since the birth of times? As Dr Hassan Ould Moctar (2021) said, “there is no one definition that is right and the other that is wrong…whatever definition we choose or agree with, that particular definition calls upon particular pieces of pieces of evidence to prove it”.

Source: Global Peace Index and Impakter

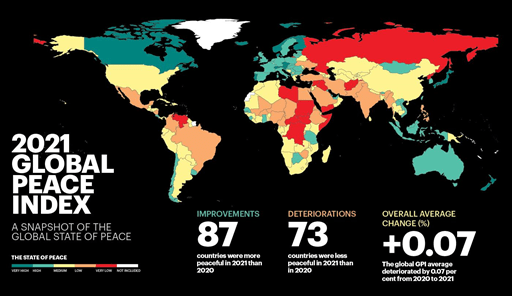

According to UNHCR, 82.4 million people were forcibly displaced at the end of 2020 due to persecution, conflict, violence and human rights violations. Furthermore, according to the Global Peace Index 2021, “this year’s results show that the average level of global peacefulness deteriorated by 0.07 per cent” (Global Peace Index, 2021). The Index further indicated that the number of conflicts has increased by 88% since 2010 and that there has been a rise in civil and political unrest – “there was a 244 per cent increase globally in riots, general strikes, and anti-government demonstrations between 2011 and 2019… There is currently no sign that this trend is abating” (Institute of Peace and Economics, 2021). Amid such numbers, it is crucial to understand that managing and dealing with conflict can lead to a more peaceful order. Moreover, as peace and conflict are linked directly – people fighting wars to ‘achieve’ peace, for example, or conflicts that lead to a lack of peace – it is imperative to know how the two are described in the literature. An interesting way that peace was described in an online document was by using the word opposite to peace – “As peace is a hypothetical construct, it is often easiest to define what peace is not—that is, conflict” (“Peace & Conflict”, n.d). This perspective is an intriguing way of looking at how the two concepts are fundamentally linked and how they exist on so many levels – whether at school, home, community, or international arenas. Within these definitions, the concept of negative and positive peace exists, as largely written about by Galtung. For Galtung, conflict was more complex than ‘trouble’ – “there is also violence frozen into structures and the culture that legitimizes this violence” (Galtung, 1996). He further added that by reducing and avoiding violence, one could hope to achieve peace. Within this context, he introduced the concepts of negative & positive peace – negative peace refers to “the absence of violence, absence of war,” while positive peace is “the integration of human society” (Galtung, 1964). According to an article on the topic of Conflict Transformation, “peace does not mean the total absence of any conflict… it means the absence of violence in all forms and the unfolding of conflict in a constructive way” (Dijkema & d’Hères, 2007). Building on this definition are authors Shtromas & Anderson, who believe that defining peace as the absence of war is flawed –“it is an ill-founded definition because it proceeds from the wrong assumption that peace and war are self-sufficient and mutually exclusive concepts which they are not” (Shtromas & Anderson, 1995). They further add that many thinkers on this subject have emphasized that “historically peace was so far only a truce cease-fire type interval between wars whose absence was yet never permanent and thus, in fact, nonexistent… politically, both peace and war are thus referring not to the essence of a relationship between various political actors but merely to its form, to the sort of instruments employed by parties involved in such a relationship” (Shtromas & Anderson, 1995). The authors thus believe that a conflictless world would not work because it is contrary to freedom. This paradigm brings us to the idea of working through conflict in a constructive way to reach a solution – yet, in many cases, easier said than done.

Source: Al Jazeera and Agence France-Presse (AFP)

As established by now, there are many variations between the definitions of terms like conflict and war and peace. Nevertheless, an important question to ask is – what do these differences translate to? The shaping of discourse through language is an important aspect here – the terms used can often demean a situation or portray it in a biased light. In Israel & Palestine, many journalists took to social media to educate their audience on how the media was wrongly portraying what was happening in Palestine. They were of the view that using terms such as ‘clashes’ or ‘conflict’ to describe what was happening in Israel and Palestine was misrepresenting the reality and ignoring the power dynamic – “This is state-sanctioned Israeli violence against Palestinians. This is settler-colonialism. This is apartheid” (IMEU, 2021). Events such as these only highlights how vital correct language usage is and how it affects the discourse. Typically, conflict is described as a disagreement or clash between two parties in the simplest of settings. However, to leave it at that is flawed. Many activists and journalists, for example, believed calling the oppression in Palestine a ‘conflict’ catered to a very problematic discourse because the word ‘conflict’ implied a disagreement between the two, while in actuality, the Israeli government was oppressing Palestinians with the possession of stronger forces, weapons, and international support. Many Palestinians also believe that calling the oppression in Palestine a ‘conflict’ is unrepresentative of the actual situation because conflict makes it seem as if they have a choice and that simply ‘talking it out’ will solve everything. This perspective is also consistent with the discourse being formed in the media, with many not recognizing the oppression for what it is – a humanitarian issue – and instead deeming the oppression in Palestine simply a conflict between Israel and Palestine. With bomb strikes, displacement issues, kidnappings, and abductions, the Israeli government has violated several human rights laws – “the Israeli government continued to enforce severe and discriminatory restrictions on Palestinians’ human rights; restrict the movement of people and goods into and out of the Gaza Strip; and facilitate the unlawful transfer of Israeli citizens to settlements in the occupied West Bank” (Humans Right Watch, 2018).

When one defines peace as simply being the ‘absence’ of war, it is ignoring events and places that are not at peace even when there is no war going on amongst them – “This negative definition, where peace becomes synonymous with non-war, deprived of a positive meaning of its own, does not account for the complexity of such a concept, nor does a utopian conceptualization that understands peace as a world in total harmony without any conflict” (Pitanguy, 2011). The author further adds that power relations act as a significant hurdle towards obtaining peace and that it is essential to understand the distinction between violence and conflict:

“Violence and conflict are not the same. Conflicts are inevitable and have been experienced by states, groups, communities, families, and individuals throughout the history of humanity. As a way to solve conflicts, violence should be contained, regulated, punished, and avoided. Peace can mean negotiating instead of confronting, using diplomacy instead of militarism, using mediation, and rejecting force to prevent or resolve conflict” (Pitanguy, 2011).

Source: Al Jazeera Middle East

Conflict & violence, however different, are closely tied together, and violence is often used in conflict-affected areas to establish control and disrupt peace. In countries where citizens are at odds with the government, they might turn to violence to get their demands across, such as in the case of South Africa, where protests turned violent after the arrest of former President Jacob Zuma. Another recent example of conflicts causing violence is the protests in Hong Kong, where riots caused chaos and police used violence to establish control. This violence resulted from unrest amongst the people by introducing the extradition bill, which could threaten judicial independence. Hong Kong and South Africa are not isolated examples; conflicts like this have always existed in the past and present and will continue to exist in the future if our attempt at resolving conflict stays the same.

In conclusion, thus, events like this only show how hard it is to define such terms and why one must understand that there is no black and white in conversations such as these; every situation is different, and reaching upon common ground seems almost impossible. However, continuing the discourse regarding this and keeping oneself informed is of utmost importance and perhaps the only way to make a difference.

This article exclusively represents the author’s views and research, not the position of The Youth Center for Research. YCR’s Habib University Chapter facilitated the curation, editing, and publishing of the article. However, the article is not an official reflection of the beliefs, views, and attitudes of the organization.

About the Author: Hafsa is a Visiting Researcher at the Youth Center for Research.

References

Peace and conflict. (n.d). Retrieved from https://www.edu.gov.mb.ca/k12/cur/socstud/global_issues/peace.pdf

Moctar, H. (2021, July). Conceptualizing Peace & Conflict. Session presented at the Summer Research Program 2021 hosted by Youth Centre for Research, Pakistan

Shtromas, A., & Anderson, G. (1995). WHAT IS PEACE AND HOW COULD IT BE ACHIEVED? [with COMMENT and REJOINDER]. International Journal on World Peace, 12(1), 15-58. Retrieved July 17, 2021, from http://www.jstor.org/stable/20752017

Pitanguy, J. (2011). Reconceptualizing Peace and Violence against Women: A Work in Progress. Signs, 36(3), 561-566. doi:10.1086/657488

Right Watch, Humans. “World Report 2019: Rights Trends in Israel and Palestine.” Human Rights Watch, 17 Jan. 2018, www.hrw.org/world-report/2019/country-chapters/israel/palestine.

Institute for Middle East Understanding [@theimeu]. Photo of IMEU. Instagram, retrieved from https://www.instagram.com/p/COn__t_Nmi-/?hl=en

D’Hère, Saint Martin, and Claske Dijkema. “Negative versus Positive Peace.” Negative versus Positive Peace – Irénées, 2007, www.irenees.net/bdf_fiche-notions-186_en.html.

Grewal, Baljit. John Galtung: Positive and Negative Peace. 2003.

Speckhard, Daniel V. “Casualties of Conflict: 7 Urgent Humanitarian Crises, The 2020 Early Warning Forecast, a Publication of Lutheran World Relief and IMA World Health – Yemen.” ReliefWeb, 2020, reliefweb.int/report/yemen/casualties-conflict-7-urgent-humanitarian-crises-2020-early-warning-forecast.

Institute for Economics & Peace. Global Peace Index 2021: Measuring Peace in a Complex World, Sydney, June 2021. Available from: http://visionofhumanity.org/reports (accessed 19 July 2021)

Galtung, J. (1996). Peace by Peaceful Means: Peace and Conflict, Development and Civilization. Prio.

UNHCR Global Trends – Forced displacement in 2020. UNHCR Flagship Reports. (2021, June 18). https://www.unhcr.org/flagship-reports/globaltrends/.

Author: Hafsa Saeed

Date: 22nd July 2021